There will be time to bury the dead. There will be time for weaponry. And there will be time to pass the time as we please, that this heroism may go on. Because now we are the masters of time.

—Mahmoud Darwish, Memory for Forgetfulness, 1982 1

1 Darwish, Mahmoud, Memory for Forgetfulness, trad. Ibrahim Muhawi, University of California Press, Berkley, 199, p.11.

Out of sight, out of mind. So goes the adage about the inextricable relation between the eye and the mind—between seeing a person or an object, and thinking about them, in a certain way, or not at all. It struck me recently that this generic saying resonates with critical approaches to visuality that have addressed the links between vision and cognition, such as the work of British art historian Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (1972). In this influential book, Baxandall posited that visual information—including representational techniques like one-point perspective—was processed differently by each viewer’s brain, while still adhering to broader historical, social, and cultural determinations. His concept of the “period eye”—a gaze situated in time and space— highlighted the links between epistemology and vision, thereby exposing the historical and cultural biases of Western perception.

By extension, “out of sight, out of mind” echoes later postcolonial and decolonial methods of visuality—those interrogating the modalities of representation distorted by Imperialism (who is entitled to represent whom? To what ends?), as in the opus Orientalism (1978) by Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Saïd. Stretching this loose thread even further, I think: “out of sight, out of mind” also recalls the relational aspect of looking (who is entitled to look? And at whom?) in a world structured by violent imperialist, colonial, and military power dynamics, as illuminated by Martinican philosopher and poet Édouard Glissant in Poetics of Relation (1990), and visual theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff in The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (2011).

Swapping “mind” with “time”, I situate the work of artist Monia Ben Hamouda within a longer art history of the Arabic-speaking world, discussing it through the combined perspectives of cultural and visual studies, as well as chronopolitics. Spanning painting, sculpture, spatial, and olfactory installations, her work may seem an unusual object for visual studies. Ostensibly material-oriented, her practice indeed centers fragrant spices, charcoal, and metals. These mutable elements affect the viewer’s experience over time, creating a break in temporality through materiality.

Yet her work engages another subtler temporal rupture. In this text, I interpret her multivalent practice in relation to strategies of resistance to visual violence and imposed chronologies. Ben Hamouda’s (re)appropriation of historical and cultural signifiers—as varied as the parietal paintings in the Lascaux caves in Dordogne, Italian Futurism, Arabic script, Islamic calligraphy—is a conscious one. This reclaiming amounts to a disruption of art history as a Western discipline influenced by time as a teleological concept—one tethered to linearity and progress, and that has reinforced racialized hierarchies between cultures.

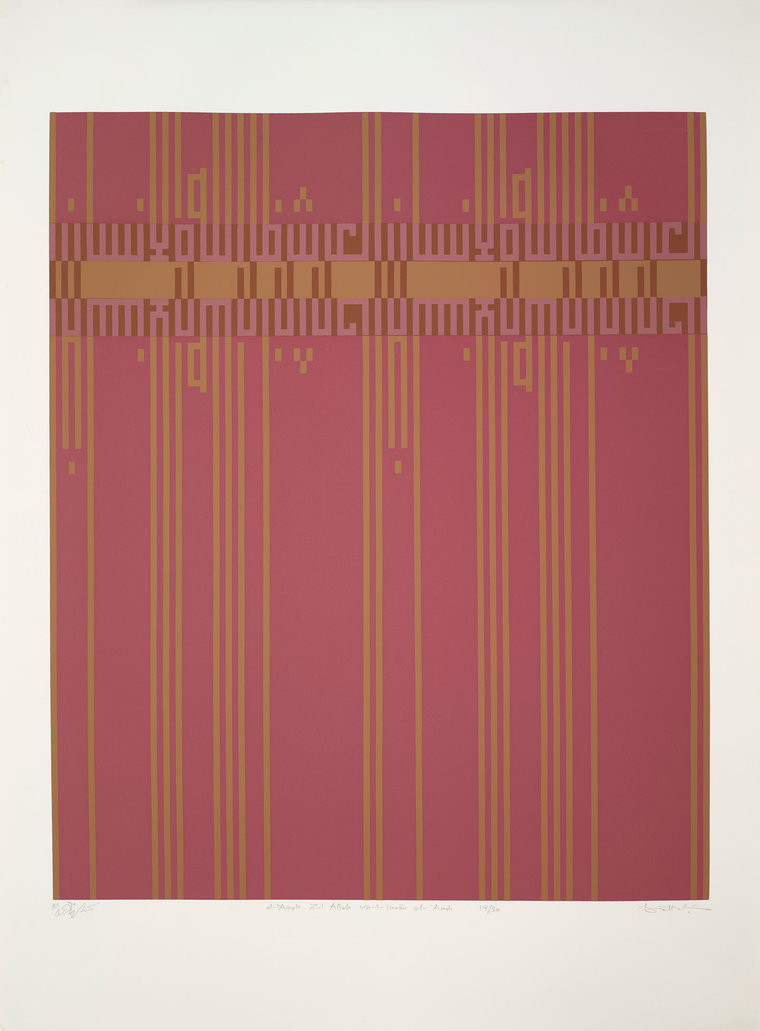

Monia Ben Hamouda, Aniconism as Figurative Urgency [Hamra], 2022. Courtesy: the artist; Ariel — Feminisms in the Aesthetics, Copenhagen; ChertLüdde, Berlin

Indeed, Ben Hamouda mobilizes these codes as images (with “images” understood here as mental conceptions rather than visual representations), mobilizing both their personal meaning, their broader cultural value, and their interpretation by Western or white audiences. In combining motifs anchored in various pasts and places, she opens new (im)possibilities of interpretation. She deploys a cultural and temporal hybridity 2

2 Throughout this text, I will refer to Homi K. Bhabha’s conception of hybridity as the mixedness inherent to cultural identity, including that of diasporic post-colonial subjects. See: Bhabha, Homi K., The Location of Culture, Routledge, London/New York, 1994.

that amounts to a form of illegibility. As such, she obscures any fixed reading of these elements, all while foregrounding her own positionality as a diasporic subject.

The essay first considers her approach to the Arabic script and letter as forms, situating it within a broader history of Islamic cultural production, as well as modern Arab and North African art. My conception of the terms “Islam” and “Islamic art and archeology” is nourished by the writings of Shahzad Bashir, Professor of Islamic Humanities, who writes that “Islam functions as an internally diverse but rhetorically unifying factor in world affairs.” 3

3 Shahzad Bashir’s interactive book, which you can skim in an open-ended way, allows you to create a different narrative of Islam and Islamic art and archaeology each time. See: Bashir, Shahzad. A New Vision for Islamic Pasts and Futures. Cambridge/London, The MIT Press, 2022, URL: https://doi.org/10.26300/bdp.bashir.ipf

Following Bashir’s findings about both historical and cultural positionalities in relation to Islamic Art, it seemed crucial to me to contextualize Ben Hamouda’s work within a longer historical arch, often comparing it to productions from decades, if not centuries ago.

As an art historian, I follow Fernando Esposito’s recommendations to consider the “chronopolitical role of historians,” and to reflect critically on “periodization [which] is chronopolitics, and [which] is also where Eurocentrism and chronocentrism meet.” 4

4 Esposito, Fernando & Becker, Tobias, “The Time of Politics, The Politics of Time, and Politicized Time: An Introduction to Chronopolitics”, History and Theory, Volume 62, No. 4, December 2023, p. 21-23.

Moreover, my interpretation is also nourished by research around other post-colonial geographies (namely South Asia), locating the work within practices from the Global Majority more broadly. This allows me to argue that Ben Hamouda’s work deftly moves between a willful and subversive process of re-orientalism, to one of illegibility—a strategy I take to be profoundly diasporic and transcultural. Later, I address the transhistorical aspect of her practice, specifically looking at the effects of combining multiple temporalities in the body of work displayed in the exhibition titled Post-scriptum—a Latin expression signifying “what is written after,” thus suggesting a futurity anchored in the past.

Approaching the Arabic letter as form: between Hurufiyya and re-orientalism?

Monia Ben Hamouda’s sculptural practice is marked by a recurrent use of iron—coiled, pierced and/or laser-cut to evoke the cursive script of Arabic calligraphy. At first glance, the informed viewer and the Arabic-reader might liken the repeated curved and flowy lines of her hanging sculptures from Aniconism as Figurative Urgency (2021–ongoing) and her sculptural panels Theology of Collapse (The Myth of the Past) (2024–ongoing) to the traditional thuluth and diwani styles of Arabic calligraphy. By stretching and abstracting these marks beyond legibility, Ben Hamouda transforms script into silhouette, evoking the very etymology of khāt, the Arabic word for “calligraphy”, which literally means “line.”

What resembles a letter becomes more of a form: lines intertwine to trace shapes that are at times abstract, and at others, ambiguously representational. They delineate shadows, delicate human hands, or perhaps animal legs. Approaching Arabic script as form might not seem to contradict the traditional art of calligraphy, used as of the 9th century for “iconographic or ornamental purposes” 5

5 Grabar, Oleg, The Formation of Islamic Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1978 (1973), p. 135.

according to Islamic art historian Oleg Grabar. Nevertheless, as Grabar notes, “whatever its abstract values visible to all, [calligraphy] very much presupposes a full knowledge of the text” 6

6 Ibid, p. 135.

—this being the sacred text of the Qur’an, as calligraphy was initially employed to record and preserve its words on buildings and in books.

Madiha Umar, The Eyes of Night, 1961, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm, Barjeel Art Foundation, Charjah © Estate Madiha Umar

Consequently, Ben Hamouda’s adaptation of the Arabic letter as form situates her practice outside of the traditional craft of calligraphy and its religious significance—not only because her appropriation of the calligraphy collapses meaning in relation to Arabic, but also because she herself does not fully master the language. 7

7 Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025.

The symbolic value of calligraphy (as a cultural form and practice reverberating in the Arabic-speaking world not only for its spiritual breadth) is still perceivable in these works, as they clearly refer to Arabic language. In that sense, Ben Hamouda’s sculptures can be inscribed within the lineage of Hurufiyya, a mid-twentieth century art movement that emerged in the Arabic-speaking world and its diasporas. With its etymology deriving from harf, meaning “letter” in Arabic, Hurufiyya drew on Arabic calligraphy’s visual vigor and cultivated the use of the letter as a “plastic element.” 8

8 Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, in Lenssen, Anneka; Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada (eds)., Modern Art in The Arab World. Primary Documents, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018, p. 142.

The roots of the movement can be found in a 1949 text by Syrian-Iraqi painter Madiha Umar who, as a student at the Corcoran Academy of Fine Arts in Washington D.C., researched the history of calligraphy, and decided to “use the Arabic alphabet as a basis for [her] my abstract painting”. 9

9 Umar, Madiha, “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949-50)”, in Lenssen, Anneka; Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada (eds)., op. cit., p. 142.

Hurufiyya spread widely in the 1960s and 1970s, as evidenced by the paintings of the Iraqis Dia al-Azzawi and Rafa Nasiri, the Palestinian Kamal Boullata, and the Algerian Rachid Koraïchi among others. The movement’s two principles consisted in “negotiating the letter as a plastic element grounded in the modernist understanding of form, and constructing a modern work of art engaged in its cultural specificity” 10

10 Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, op. cit., p. 142.

, as analyzed by art historian Nada Shabout.

Rafa Nasiri, Untitled, 1981, color etching, aquatint and viscosity printing on paper, 57.5 x 78 cm, Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut.

It is worth noting that the works of these artists varied from pure graphic abstraction (as seen in the work of Boullata) to a more expressionist take on figuration that integrated abstract elements (as in the paintings of Nasiri)—an aspect which resonates with Ben Hamouda’s similarly fluid treatment of sculpted metal. This genealogy clarifies the stakes of Ben Hamouda’s practice. Like in Hurufiyya, the letter does not interest her as a vehicle of semantics, nor as a mere form, but as an emblem of cultural value.

Indeed, the Hurufiyya artists were emboldened by the pan-Arabism and secularism of the period, which led them to take on the letter as a “signifier of Arab identity”. For them, the letter-as-form eluded calligraphy’s religious past and disrupted the Western archeological fascination with it—an obsessive fetishization that cannot be separated from the colonial and imperialist impetus behind the discipline of archaeology 11

11 For a summary on the impact of colonial and post-colonial regimes in the production of archeological knowledge in the Arab world, see: Munawar, Nour Allah, “Time to decolonise: ‘If not now’, then when?”, Journal of Social Archaeology, Volume 24, Issue 1, 2024, p.3-12, URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/14696053231224321. For a more accessible, albeit prescient, discussion on the entanglements of Islamic Art and Archaeology, colonialism, and war, see: Rabbat, Nasser, “On Art History in Times of War”, Art in America, June 5, 2025, URL: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/columns/on-art-history-in-times-of-war-gaza-islamic-nasser-rabbat-1234744329/

. In these artists’ view, removing the religious from calligraphy and semantics from language turned the letter into “a decolonized form.” 12

12 Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, op. cit., p. 142.

Kamal Boullata, El Arsh Zil Allah wa’L Insan Zil Allah, 1983, color silkscreen on paper, 76 x 56 cm, Dalloul Art Foundation, Beirut.

Code-switching: the trap of re-orientalism, reckoning with the diasporic, and toying with Futurism

Ironically, the legacy of Hurufiyya partially betrayed its decolonial incentive. The very name of the movement eventually became an umbrella-term that not only designated masterpieces of the genre, but also decorative iterations of Arabic writing. The latter circulated as commodities in the Western art market especially in the early 2000s, conforming to neo-Orientalist tropes and expectations. To contextualize Ben Hamouda’s practice within this fraught post-colonial landscape, it is necessary to tackle her positionality. Her seemingly formalist adaptation of language inevitably raises political questions of identity, address, and reception—whether by the market or the institutional apparatus. Ben Hamouda is a Tunisian-Italian artist, born in a Muslim community in Milan, who now divides her time between her native city and al-Qayrawan in Tunisia. This dual anchoring affords her visibility in both the Global Majority and the West, positioning her squarely within the condition of the diasporic global artist. I mention these parameters as they are essential to understand the address in her practice: from where, and to whom, does her engagement with Arabic script speak?

Crucially, Ben Hamouda chose a language she does not completely grasp as her main motif. In doing so, she playfully treads the fine line of what literary critic and interdisciplinary geographer Lisa Lau has dubbed “re-orientalism.” 13

13 Lau, Lisa, “Re-Orientalism: The Perpetration and Development of Orientalism by Orientals”, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2009, pp. 571-590, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20488093

Drawing on Edward Saïd’s definition of orientalism as an othering process centering a Western gaze that objectifies its “Oriental” subject, Lau re-actualized it by observing that diaspora cultural production could reproduce similar dynamics. In particular, South Asian writers based in the West often gained disproportionate prominence over “home authors,” 14

14 Ibid, p. 575.

or locals that wrote from/in South Asia, thus circulating selective cultural images that were generalized as normative. The result, Lau argued, was a new form of Orientalism enacted by diasporic subjects themselves and that “reinforced fables and stereotypes.” 15

15 Ibid, p. 582-584.

Monia Ben Hamouda, Hitting [Aniconism as Figurative Urgency], 2023; laser-cut iron, spice powders; 209 × 141 × 0.03 cm

Ben Hamouda’s position is more complex. The daughter of a Tunisian calligrapher with roots in Italy as well, she acknowledges that, despite the knowledge transmitted by her father, she grew up “partially outside of both a [Arabic] language and a [Arab] culture,” which taught her that this “‘outsideness’ can be a place of freedom and invention, not only of loss.” 16

16 Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025.

In light of her familial and cultural belonging, Ben Hamouda recognizes the specificity of her positionality as a diasporic subject: her words (specifically her use of the term “outsideness”) resonate with the writings of Indian critical theorist Homi K. Bhabha on the centrality of in-betweenness in cultural identity, namely for diasporic subjectivities. Ben Hamouda also admitted wanting to re-create her own experience of the language: “In my work, I want to bring viewers into a similar position: unable to read or “translate” the language in front of them, but still recognizing it as language.” 17

17 Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025.

Beyond this reckoning—which contributes to the resistance of Ben Hamouda’s work to the pull of re-orientalism—, it is worth noting that her practice leaves behind a trail of hints that signal a deep knowledge of her subject. In that way, her evocation of Arabic script cannot be labeled as stereotypical. This is evident in the subtle antinomy in the title of her series Aniconism as Figurative Urgency: the wording admits the centrality of aniconism (or the prohibition of figuration), one of the original principles of Islam that fueled the emergence of stylized abstract decorative motifs. Additionally, the title mirrors the findings of Madiha Umar’s early reflections on what would become Huruffiya, which traced the origins of calligraphy’s centrality in Islamic art to this religious prohibition. 18

18 Umar, M., “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949-50)”, op. cit., p. 141.

These elements point to a cultural literacy that only those in the know will recognize.

Ben Hamouda further complicates and layers her visual and historical repertoire in the panels Theology of Collapse (The Myth of the Past), leaning elegantly on the gallery’s walls. A sequence of forms that seem to derive from Arabic script multiply on these four panels. The irregularity of the composition echoes certain characters of Najdi poetry—a vernacular, oral tradition, whose earliest iterations roughly date to the end of the 14th century, but that fully flourished in the 16th century. Citing the structures, rhythm, and themes recurring in pre-Islamic poetry, this tradition is rooted in the Arabic peninsula, where nomadic poets would recite their verses as they moved on the backs of horses. Ben Hamouda’s repeated shapes also give the impression of animals in motion, a visual motif that the artist links to the idea of a “travelling language,” 19

19 Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025.

as exemplified by Najdi poetry. But this motif also recalls a resolutely Western tradition, one that relates to the artist’s other culture. Indeed, the reiteration of similar forms to evoke velocity is reminiscent of Giacomo Balla’s Dinamismo di un cane al guinzaglio (1912), and the work of early twentieth-century Italian Futurism more broadly. 20

20 For a thorough discussion of Ben Hamouda’s work in relation to Italian Futurism, see: Ragazzi, Francesco, “No One is a Prophet. Monia Ben Hamouda and the Writing of the Undecidable”, MAXXI BVLGARI PRIZE 2024 Riccardo Benassi, Monia Ben Hamouda, Binta Diaw, Roberto Fassone for digital art, MAXXI, Rome, 2024.

Giacomo Balla, Dinamismo di un cane al guinzaglio [Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash], 1912, oil on canvas, 89,9 x 109,8 cm, Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo, New York, © Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York/SIAE Rome.

This layering of multiple cultural and historical references—shifting astutely between Arabic script, Islamic aniconism, pre-Islamic influences, and Western avant-garde aesthetics that have proven links to fascism in Italy—crystallizes what I would call a diasporic code-switching. Rather than merely alternating between two cultural registers, her practice multiplies them, folding disparate genealogies into forms that refuse closure. As such, this work enacts a form of “in-betweenness,” 21

21 Bhabha, Homi K., The Location of Culture, Routledge, London/New York, 1994.

a central aspect of Bhabha’s definition of cultural hybridity, who writes: “It is in the emergence of the interstices—the overlap and displacement of domains of difference—that the intersubjective and collective experiences of (…) cultural value are negotiated.” 22

22 Ibid, p. 2.

It is indeed a negotiation of cultural values, anchored in different and somewhat mythologized pasts, that is at the core of Ben Hamouda’s Theology of Collapse (The Myth of the Past). The work melds a subversive re-orientalism with an equally iconoclastic appropriation of Futurism—strategies that allow her work to not yield fully the viewer.

By multiplying her cultural and temporal referentials, Ben Hamouda then foregrounds illegibility as a visual strategy: both Theology of Collapse (The Myth of the Past) and Aniconism as Figuration Urgency culminate in “the active production of a visible but unreadable image,” 23

23 Britton, Celia M., Edouard Glissant and Postcolonial Theory: Strategies of Language and Resistance, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1999, p. 24.

to quote Celia M. Britton, a literary critic and scholar of Caribbean literature. Her words explicate Édouard Glissant’s argument on “the right to opacity,” or the willful withdrawal of information from the extractive and totalizing Western gaze. Similarly, Ben Hamouda’s work refuses to render these references transparent: by subtly changing them and then layering them. By deploying illegibility as an artistic strategy, she opens up what she calls “an active, generative space where the work can exist without the need to be ‘resolved’.” 24

24 Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025.

By refusing transparency, she indeed interrupts the extractive logics of both the art market and institutional discourse, positioning her work instead in a zone of continual negotiation and untranslatability. Yet Ben Hamouda’s conception of the “untranslatable” does not adhere to the idea of an irreducible singularity 25

25 Irreducible singularity (Heideggerian philosophy) : the idea that a word cannot be translated or really should not be translated, because to translate it is to violate it in some way or to violate the culture from which it comes. — explicited by Rebecca L. Walkowitz

—whether in language or culture more broadly. In fact, her strategy of illegibility could be compared to French philosopher Barbara Cassin’s definition of the “untranslatable” as that which you can never cease to translate, implying a continuous process of adaptation. 26

26 Walkowitz, Rebecca L., “Translating the Untranslatable: An Interview with Barbara Cassin”, Public Books, June 15, 2024, URL: https://www.publicbooks.org/translating-the-untranslatable-an-interview-with-barbara-cassin/

Layered temporalities and structures of repeatability: towards the transcendental

Just as she obscures her cultural references, Monia Ben Hamouda blurs her historical and temporal citations. This summoning of historical times appears clearly in the painting series Blindness, Blossom and Desertification (2023–ongoing) and A Burst of Light (2024–ongoing). On the dark brown linen canvas, pigments, and spices with healing effects (such as chili powder, paprika, hibiscus, and cinnamon) are turned into beige, burgundy, crimson, and rust-colored swirls. This earthy color palette and these sinuous forms are quoting the silhouettes of animals drawn in the Lascaux cave paintings.

Yet Ben Hamouda’s work and the Lascaux paintings share more than their visual qualities: she also cites, whether consciously or not, the processes underlying the striking forms. In that sense, this reference signals a double relationship to time: first to pre-historical time, and then to the very temporality of the artwork. Indeed, the Lascaux paintings can be considered as some of the earliest palimpsests 27

27 A manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing.

in history, wherein multitude of signs, drawn by different makers at distinct moments, are superimposed on their surface. From figures and animals, to weapons specific to the Upper Paleolithic, and even abstract marks, these parietal compositions are the accumulation of different periods, as well as various makers. Strikingly, it seems that these painters were careful enough to leave the traces of their predecessors visible, as noted by philosopher Fiona Hughes. Hughes remarks: “it is as though figures were meant to be seen together in the complexity of their relations or, when conditions suggest vision of underlying layers would have been restricted, as if the superimposing forms were constructed so as to leave the underlying figure intact whether it was seen or not (…).” 28

28 Hughes, Fiona, “The Temporality of Contemporaneity and Contemporary Art: Kant, Kentridge and Cave Art as Elective Contemporaries”, in Kantian Review, Vol. 26, p. 597, URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/

Likewise, Ben Hamouda’s paintings are constructed through multiple strata—of references, matter, and epochs—, ultimately amounting to a layered temporality.

Monia Ben Hamouda, Blindness, Blossom and Desertification [Diptych VIII], 2025, soil, clay, charcoal, cinnamon on raw linen, 350 x 285 cm

Noticing the striking transhistorical similarities between Ben Hamouda’s contemporary works and the pre-historic paintings, I turn to the German historian Reinhart Kostelleck who wrote critically on the politics of time in relation to history and historiography. In his 2018 book Sediments of Time: On Possible Histories, Kostelleck finds both the teleological and the cyclical conceptions of time to be insufficient—preferring instead to acknowledge the relevant aspects of each, and to borrow metaphorically from the field of geology. Indeed, he posits that “Historical times consist of multiple layers that refer to each other in a reciprocal way,” with certain patterns (of form, of thought) acting like sediments. Central to his argument are the “structures of repeatability,” 29

29 Kostelleck, Reinhart, Sediments of Time: On Possible Histories, Stanford University Press, California, 2018, p. 4.

which extend over different periods and generations—of thinkers, makers, and objects. These structures of repeatability allow the re-emergence of patterns, much like sediments circulating between different layers of earth, and highlight the transcendental quality of historical productions. Within this concept of (art historical) time, the links between the ultra-contemporary work of Ben Hamouda, and the pre-historic parietal paintings in Dordogne, or 9th century Arabic calligraphy, are not merely citational: they emanate from the return of certain “religious and metaphysical truths.” 30

30 Ibid, p. 8.

This statement resonates with the artist’s own description of her working process as one of shamanism, wherein Ben Hamouda confronts the spirits of her cultural heritage through her artistic practice.

A past anchored in futurity

That a body of work, echoing transcultural and transhistorical approaches to art, is united under the title Post-scriptum is telling. Indeed, the Latin expression, meaning “written after,” inherently gestures to futurity anchored in the past—a supplement that disrupts linear chronology by re-inscribing what came before. It thus encapsulates the temporal logic running through Ben Hamouda’s exhibition: a refusal of teleology in favor of layering and recurrence.

More than a transcultural strategy, the artist’s melding of references from different epochs also signals a transhistorical approach. This aspect becomes even more evident once we consider these works all together, as one corpus. The space constructed by Ben Hamouda is one where pre-Islamic references, influential for 18th century oral poetry, coexist with calligraphy, whose beginning can be dated to the 11thcentury. This space goes back even further in time, citing what occurred before history, or even, those who have slipped outside of living time. In fact, Ben Hamouda’s interpretation of the expression “Post-scriptum” brings us back to her own conception of her artistic labor as one of shamanism— a metaphysical endeavor then, that is not only concerned with historical and cultural objects, but also persons.

Ultimately, she displaces these various signifiers “out of time”, or to put it differently, delivers them from a teleological approach to art, and a reductive vision of cultures which come from/speak of hybridity. Monia Ben Hamouda reminds us that we too can be “the masters of time”. 31

31 Darwish, Mahmoud, Memory for Forgetfulness, op. cit.

- Darwish, Mahmoud, Memory for Forgetfulness, trad. Ibrahim Muhawi, University of California Press, Berkley, 199, p.11. []

- Throughout this text, I will refer to Homi K. Bhabha’s conception of hybridity as the mixedness inherent to cultural identity, including that of diasporic post-colonial subjects. See: Bhabha, Homi K., The Location of Culture, Routledge, London/New York, 1994. []

- Shahzad Bashir’s interactive book, which you can skim in an open-ended way, allows you to create a different narrative of Islam and Islamic art and archaeology each time. See: Bashir, Shahzad. A New Vision for Islamic Pasts and Futures. Cambridge/London, The MIT Press, 2022, URL: https://doi.org/10.26300/bdp.bashir.ipf []

- Esposito, Fernando & Becker, Tobias, “The Time of Politics, The Politics of Time, and Politicized Time: An Introduction to Chronopolitics”, History and Theory, Volume 62, No. 4, December 2023, p. 21-23. []

- Grabar, Oleg, The Formation of Islamic Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1978 (1973), p. 135. []

- Ibid, p. 135. []

- Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025. []

- Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, in Lenssen, Anneka; Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada (eds)., Modern Art in The Arab World. Primary Documents, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018, p. 142. []

- Umar, Madiha, “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949-50)”, in Lenssen, Anneka; Rogers, Sarah, and Shabout, Nada (eds)., op. cit., p. 142. []

- Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, op. cit., p. 142. []

- For a summary on the impact of colonial and post-colonial regimes in the production of archeological knowledge in the Arab world, see: Munawar, Nour Allah, “Time to decolonise: ‘If not now’, then when?”, Journal of Social Archaeology, Volume 24, Issue 1, 2024, p.3-12, URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/14696053231224321. For a more accessible, albeit prescient, discussion on the entanglements of Islamic Art and Archaeology, colonialism, and war, see: Rabbat, Nasser, “On Art History in Times of War”, Art in America, June 5, 2025, URL: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/columns/on-art-history-in-times-of-war-gaza-islamic-nasser-rabbat-1234744329/ []

- Shabout, N., “Huroufiyah: The Arabic Letter as Visual Form”, op. cit., p. 142. []

- Lau, Lisa, “Re-Orientalism: The Perpetration and Development of Orientalism by Orientals”, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2009, pp. 571-590, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20488093 []

- Ibid, p. 575. []

- Ibid, p. 582-584. []

- Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025. []

- Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025. []

- Umar, M., “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949-50)”, op. cit., p. 141. []

- Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025. []

- For a thorough discussion of Ben Hamouda’s work in relation to Italian Futurism, see: Ragazzi, Francesco, “No One is a Prophet. Monia Ben Hamouda and the Writing of the Undecidable”, MAXXI BVLGARI PRIZE 2024 Riccardo Benassi, Monia Ben Hamouda, Binta Diaw, Roberto Fassone for digital art, MAXXI, Rome, 2024. []

- Bhabha, Homi K., The Location of Culture, Routledge, London/New York, 1994. []

- Ibid, p. 2. []

- Britton, Celia M., Edouard Glissant and Postcolonial Theory: Strategies of Language and Resistance, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 1999, p. 24. []

- Interview with the artist over email, August 12, 2025. []

- Irreducible singularity (Heideggerian philosophy) : the idea that a word cannot be translated or really should not be translated, because to translate it is to violate it in some way or to violate the culture from which it comes. — explicited by Rebecca L. Walkowitz []

- Walkowitz, Rebecca L., “Translating the Untranslatable: An Interview with Barbara Cassin”, Public Books, June 15, 2024, URL: https://www.publicbooks.org/translating-the-untranslatable-an-interview-with-barbara-cassin/ []

- A manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing. []

- Hughes, Fiona, “The Temporality of Contemporaneity and Contemporary Art: Kant, Kentridge and Cave Art as Elective Contemporaries”, in Kantian Review, Vol. 26, p. 597, URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/ []

- Kostelleck, Reinhart, Sediments of Time: On Possible Histories, Stanford University Press, California, 2018, p. 4. []

- Ibid, p. 8. []

- Darwish, Mahmoud, Memory for Forgetfulness, op. cit. []